Hey guys, Tyler here. The warp drive is a core technology in Star Trek that enables faster-than-light travel. It makes interstellar civilization, exploration, and commerce possible, and by the 24th century, it is the primary means of interstellar transport throughout the Milky Way.

But as we see, while humans invent it in the mid-21st century, various cultures have had warp technology for much longer. Travelling faster than light would normally violate the laws of physics and Einstein’s theory of general relativity, but some theoretical physicists believe there may be ways to get around that. The question is, however, could we build something like a warp engine in real life?

Today, I’ll attempt to answer this and other questions…let’s get started.

Warp Mechanics

Before we can explore the prospect of breaking the light barrier in our world, let’s first get a better grasp on how warp drives operate in Star Trek. While The Original Series does provide some fundamental details about how warp drives function, more attention is given to the process in The Next Generation era and beyond.

Starfleet warp engines, at least, are fueled by a matter/antimatter reaction. The matter in this reaction is deuterium, a stable isotope of hydrogen that, in addition to the single proton that characterizes normal hydrogen, contains a single neutron as well.

Thus, deuterium is sometimes called “heavy hydrogen.” And naturally, the antimatter component of the reaction is called antideuterium. You may remember from science class, or if not from there, then maybe from YouTube or Wikipedia, that when matter and antimatter collide, they tend to, well, annihilate each other, producing a nuclear explosion.

This is where Dilithium crystals, which regulate the matter/antimatter reaction, come in. Whereas in real life, Dilithium is a gaseous molecule composed of two lithium atoms, in Star Trek, Dilithium is a full-fledged crystalline element that is part of the so-called “hypersonic series.”

Since real lithium, being a metal, cannot form solid diatomic molecules, one explanation given in Trek is that Dilithium has a subspace component that keeps it stable despite its high atomic weight—possibly the reason it can’t be synthesized or replicated.

As far as I can tell, the closest we’ve come to being given an atomic number and weight for this element is 119 and 315, respectively, from the Star Fleet Medical Reference Manual. The novels Prime Directive and Firestorm also confirm Dilithium’s quartz-like structure and identify 2-3% of Earth’s quartz as being useful for regulating the antimatter reaction in warp cores. In canon, we know that rare natural deposits of Dilithium exist throughout the galaxy, and its rarity thus makes it a highly valuable substance.

Dilithium crystals are nonreactive with antimatter when subjected to high-frequency electromagnetic fields. This reaction produces highly energetic plasma called warp plasma, which is channelled by plasma conduits through the electro-plasma system, or EPS.

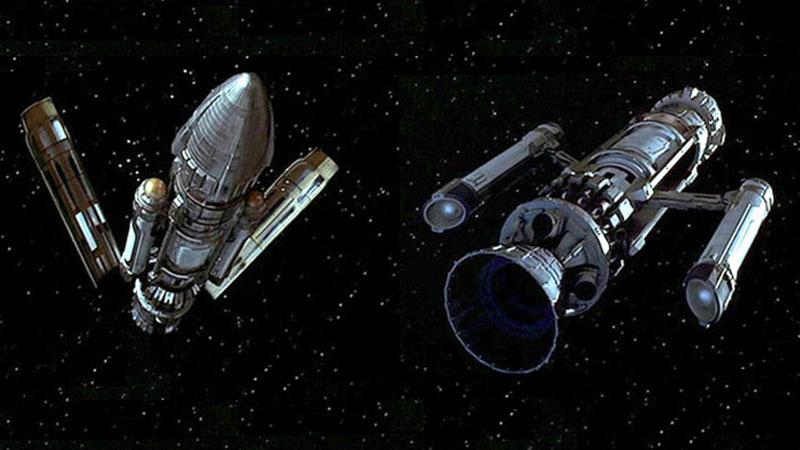

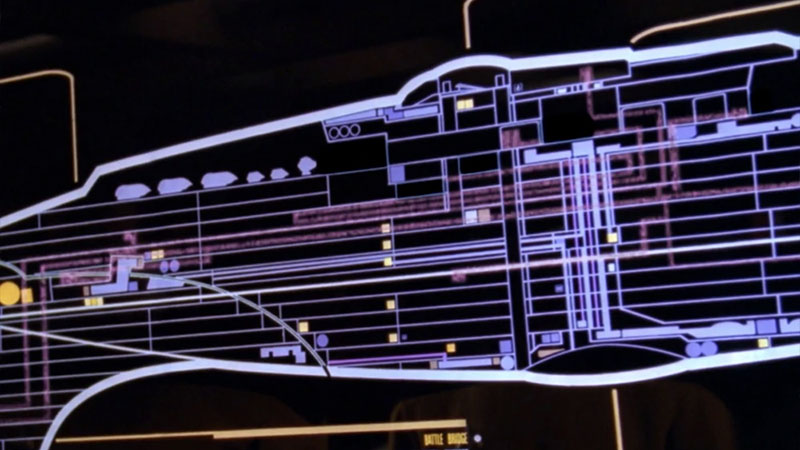

The EPS also provides the primary energy supply for the ship’s other electronic systems. For propulsion, plasma injectors funnel plasma into a series of warp field coils, usually located in the warp nacelles—the cylindrical structures behind the saucer section connected by pylons to the secondary hull.

These coils are typically composed of a cast of the fictitious material verterium cortenide, a dense alloy of silica-based polymers and crystals, and the cast surrounds a tungsten-cobalt-magnesium core. The coils then create a subspace displacement field around the ship, allowing it to travel at warp speed. The field also has the physical effect of reducing the inertial mass of any object within its volume.

It’s this displacement field that honestly forms the crux of why warp drive is even effective as a faster-than-light propulsion method. As we are reminded by the 2009 Star Trek film, it’s not really the ship that’s moving faster than light—because that’s impossible—but space itself…kinda.

According to special relativity, because the speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers, to preserve causality, no information or material object can travel faster than light. The speed of light c, or 300,000 km/s (186,000 miles per second), is essentially the cosmic speed limit.

But this isn’t to say that nothing can “happen” faster than light—in fact, the expansion of spacetime itself under cosmic inflation can and does happen much faster. Therefore, the radius of the observable universe is over 46 billion light-years, even though the universe is only 13.8 billion years old. And the whole universe, beyond our “cosmic horizon,” may be trillions of light-years across.

So, by taking advantage of the fact that space can expand or contract, a warp drive can allow an object to “coast” along the subspace distortion to reach its destination intact. The object would thus bypass the effects of time dilation, which general relativity says all objects travelling close to the speed of light experience.

That said, sometimes we do see the ship’s chronometers correct for very small variations just like satellites orbiting the Earth do. And indeed, on occasion, we see starship crews take advantage of the “normal” spacetime properties inside warp bubbles to connect the warp fields of multiple ships, such as in the Enterprise episode “Divergence.”

But the problem with all of this—even the creation of a stable warp field in the first place—is that such a process would require LOTS of energy, more energy than we’ve frankly ever been able to harness at once in the lifetime of our civilization. This leads to the question…are warp drives even theoretically possible, and even if they are, are they practical?

The Need for Speed

Before we can talk about skirting the laws of physics, let’s first establish how fast we can go with our current technology. It may come as no surprise that, in the present day, the fastest speed we’ve been able to achieve with any man-made object is…much slower than the speed of light.

Like, by orders of magnitude. The fastest object that we have ever built is the Parker Solar Probe, launched by NASA in 2018. In February 2020, Parker set a record by travelling at 244,255 mph (393,044 km/h)[1], and about a year and a half later, according to Guinness World Records, it broke its own record by travelling at 364,660 mph (586,800 km/h).

And yet, this is only .0005% the speed of light. Think of how fast a helicopter or a bullet train is, okay? Now, that’s a thousand times slower than the Parker Solar Probe, which itself is two thousand times slower than the Phoenix, humanity’s first warp vessel as seen in Star Trek: First Contact.

So, we’ve got a long way to go before we can build a warp drive. But that hasn’t stopped real-world theoretical physicists from speculating about how we could build one. Arguably the most popular faster-than-light engine concept outside of science fiction is the Alcubierre drive.

Named after physicist Miguel Alcubierre, this speculative device would mimic the expansion and contraction of spacetime like in Star Trek by creating a negative energy-density field. Though this method is consistent with Einstein’s field equations, there are…other hurdles. Creating an energy-density field below that of a vacuum requires a little thing called negative mass, a type of “exotic matter.”

Now, the exotic matter might sound too good to be true, but broadly speaking, it is a thing—dark matter, for example, falls under this category, as do various particles and rare states of matter that have either been experimentally confirmed or are otherwise in line with the Standard Model.

In fact, Alcubierre has suggested that the Casimir vacuum—a region of negative pressure density produced by the Casimir effect, which arises from quantum fluctuations in elementary particle fields—could fulfil the energy requirements for a warp drive.

This argument follows the same principles as analyses by other physicists regarding traversable wormholes. Some research has even claimed that the Alcubierre drive is possible with purely positive energy with the use of “soliton” waves, which retain their shape even while propagating at a constant velocity.

That said, other physicists have argued a complete theory of quantum gravity, which combines relativity with quantum mechanics, would eliminate the possibility of backwards time travel and other weird effects, including the artificial spacetime curvature associated with warp drives.

One fact that does make this all worth it, though, is that Miguel Alcubierre’s warp drive was directly inspired by Star Trek, which he has been open about since the original 1994 article detailing his hypothesis. So, there you go: Star Trek always has and will continue to inspire real people to push the boundaries of science.

Okay, back down to Earth…to say that the Alcubierre drive relies on an ability to manipulate matter, energy, and spacetime far beyond our current capabilities is an understatement. But in recent years, researchers have concluded that the amount of energy needed to power it is “no longer thought to be unobtainable large,” as in more energy than the combined mass of the observable universe.

As per his paper titled “Warp Field Mechanics 101,” Harold G. White recalculated the Alcubierre concept in 2011. He proposed that if the warp bubble around a spacecraft were shaped like a torus, or “doughnut,” it would be significantly more energy-efficient and thus make the whole concept closer to feasible.

White’s team followed up in 2012 with another study that showed that modifying the geometry of exotic matter could additionally reduce the mass-energy requirement for a macroscopic spaceship from the equivalent mass of the planet Jupiter to that of the Voyager 1 spacecraft (or Voyager 6 if you’re more Trek-inclined).

That’s progress right there. The study demonstrated, however, that focusing less energy on a larger volume would still leave less “flat” space to house the spacecraft, which must logically be smaller. This is in line with what we see in Star Trek as far as warp-capable ships getting bigger over time as technology improves, effectively a reversal of the process of miniaturization.

Regardless, Alcubierre has expressed scepticism at this idea, saying this specific method of creating a larger warp bubble with less energy cannot be done, “probably not for centuries if at all.”

In fact, this could be applied to the entire concept of warp drives—the idea that we will break this barrier in the 21st century is highly unlikely given everything that we currently know. Some believe we may not break the light-speed barrier for another thousand years, or even a MILLION years.

And of course, the Alcubierre drive has lots of other difficulties that cause it to violate various energy conditions. Some believe a warp journey could only work if the vessel’s entire path were curved ahead of time, with such infrastructure likened to a railroad. Therefore, Star Wars has pre-mapped “Hyperspace Lanes,” for example.

Others believe that anything inside a warp bubble would be vaporized by Hawking radiation. Even if we can build starships that run on fusion power or even antimatter, journeys to other stars may always be limited to several years rather than weeks, days, or minutes.

Proponents argue it is possible, however, to bypass these problems by taking advantage of quantum mechanical phenomena…like the Casimir effect. Scientists have long proposed experiments to create small warp bubbles in a lab, so to me, that signals that we should not give up hope yet. So, to answer the question: “could we build a warp drive?” Likely not this century, maybe not even this millennium, but eventually? Perhaps.

If you want to support my work even further, becoming a patron at patreon.com/orangeriver is a great way to do so.

Watch The Latest Video By Orange River Media Below

Thank you all so much for watching. I’m really interested to hear your thoughts in the comments.

If you enjoyed this video, be sure to leave a thumbs up down below and don’t forget to share it. That stuff really helps me out. If you haven’t subscribed, be sure to do that as well and click the bell icon to receive all notifications.

That’s all I have for this week…live long and “Engage!”

You can find Orange River Media at the links below

- YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/orangeriver

- Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/orangerivernw

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/orangeriver.nw

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/orangerivernw

- Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/orangeriver