Hey guys, Tyler here. For decades, humanity has had at least a semi-continuous presence in low Earth orbit, with various space agencies making use of artificial habitats that we refer to as space stations. In Star Trek, the most frequently featured type of space station is a Federation facility known as a “Starbase.”

Starbase’s are large facilities run by Starfleet that serve numerous purposes, whether it’s starship construction, scientific research, supply storage, military, and diplomatic installations, living spaces, etc.

But How Do They Actually Work?

That is, how are Starbase themselves constructed, how can they house so many facilities, and could we reasonably build something like them in real life? Those are the questions I will attempt to answer in this video.

First things first, a little real-world background. The first launch of a manned space station was the Soviet Union’s Salyut-1 in 1971, and it was followed by NASA’s Skylab in 1973, the Soviet Union’s Mir in 1986, the International Space Station in 1998, and China’s Tiangong stations starting in 2011.

But for over a century before Skylab went up, man had dreamed of working and living in space. Science fiction of the mid-20th century offered some stunning depictions of what we could accomplish, with standout examples including 2001: A Space Odyssey and, of course, Star Trek.

Before we go any further, I also want to clarify something. The term “Starbase” refers to a collection of facilities, not just the space station itself. Starbase’s can also include drydock repair facilities as well as ground installations. The term drydock is usually synonymous with “Spacedock,” but Spacedocks can also be part of space stations…it gets a little confusing.

In this article, however, I’ll be talking specifically about the space stations, and I might cover the shipyards and ground installations in separate videos. With that out of the way, let’s get started.

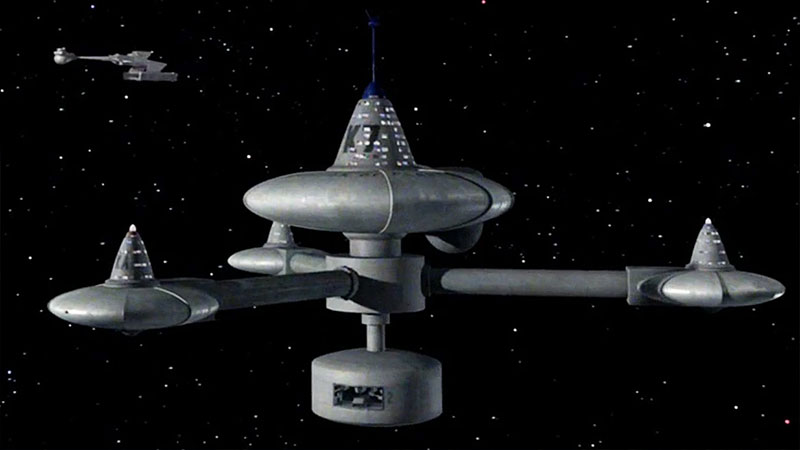

One thing that immediately stands out about the space stations: these things are HUGE. They absolutely dwarf the starships that enter and exit their massive docking bays, and those starships are often hundreds of meters long. As we learn in the commentary for Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Earth Spacedock was imagined as having a total height of over three miles, or over 4.8 kilometres.

The 2001 reference book Star Trek: Starship Spotter roughly corroborates this, putting the station’s height at 4.6 kilometres. At this size, it would be visible to the naked eye from Earth’s surface, and in fact, in Star Trek: Picard, we see Spacedock-looking orbital facilities very high in the sky. With this height, it’s easy to see how such a station could easily house as many as 80,000 civilians and Starfleet personnel.

However, how does such a thing stay in orbit? To some, this may be a silly question to ask—after all, the International Space Station is…oh…73 meters…that’s…I thought it was bigger. So yeah, how does Spacedock stay in orbit? Being in low Earth orbit, the ISS is in a perpetual state of freefall, in fact, astronauts aboard it experience 90% of the gravitational pull they’d experience at ground level.

So, it must use thrusters to keep from descending into Earth’s atmosphere. So, the answer is quite simple when it comes to bigger space stations: bigger thrusters! Specifically, Spacedocks would make use of the same kind of impulse engines that a starship would—and by the way, “impulse” is Star Trek’s fancy way of saying “fusion power.” These impulse engines enable sublight propulsion by venting plasma exhaust through the EPS, or electro-plasma system, via EPS conduits.

The source of this plasma is specified to be a fusion reactor system, which on a Galaxy Class starship is located between decks 23 and 25. It’s separate from the main warp core, which uses antimatter, although the warp core also produces plasma that can be diverted through the EPS to the power transfer grid. One schematic of Earth Spacedock from Stardate Magazine also shows it with antimatter engines, meaning the antimatter core could produce the sufficient plasma needed to power impulse thrusters.

I won’t get too into the weeds when it comes to propulsion, that may also be covered in a separate article but suffice it to say, the humongous space stations we see in Star Trek would require LOTS of energy, and LOTS of raw materials. The number of raw materials is hard to put a numerical value on, but it would certainly make use, in my estimation, of the countless mining operations on asteroids, moons, and planetoids that undoubtedly exist throughout Federation space.

That said, it shouldn’t be forgotten that much of a space station’s volume would be composed of empty space, particularly when it comes to the docking hangars behind those gigantic doors we see opening and closing throughout lots of the films. According to schematics from Stardate Magazine as well as the game Star Trek Online.

Below the docking bay, on the “lower decks,” if you will, are living quarters, a hospital, commercial areas and offices, hotels, recreation facilities, storage, life support, and a communications hub. One non-canon source also suggests that when Earth Spacedock was being constructed, United Earth objected to the planned installation of weapons systems on the station, so they were never installed, with the station instead of relying on strong shields for protection.

This may be why Earth often needs crewed starships to defend the Sol system, and those ships are often in other sectors, meaning it takes time for Earth’s defences to come to the rescue. It should be noted, of course, that in canon, we don’t know the exact nature of the facilities below the docking bays nor Spacedocks true dimensions, so all of this should be taken as one possible explanation for how these space stations are used.

Some sources list Earth Spacedock as Starbase 1, but this doesn’t really seem to be the case. In Discovery season 2, we learn that at least in the mid-23rd century, “Starbase 1” is a separate space station about 100 AUs from Earth, about twice the distance of Pluto from the Sun. And it also has a crew and civilian complement of 80,000 individuals, Or, well, at least it did until it was attacked and occupied by the Klingons during the Federation-Klingon War.

It was later rebuilt, as we learn in Star Trek: Picard. Before being featured in Discovery, “Starbase 1” was a designation that was originally going to be reserved for one of Earth’s first extrasolar space stations in orbit of Berengaria VII. This was to be featured in an episode of Enterprise’s ultimately unproduced fifth season.

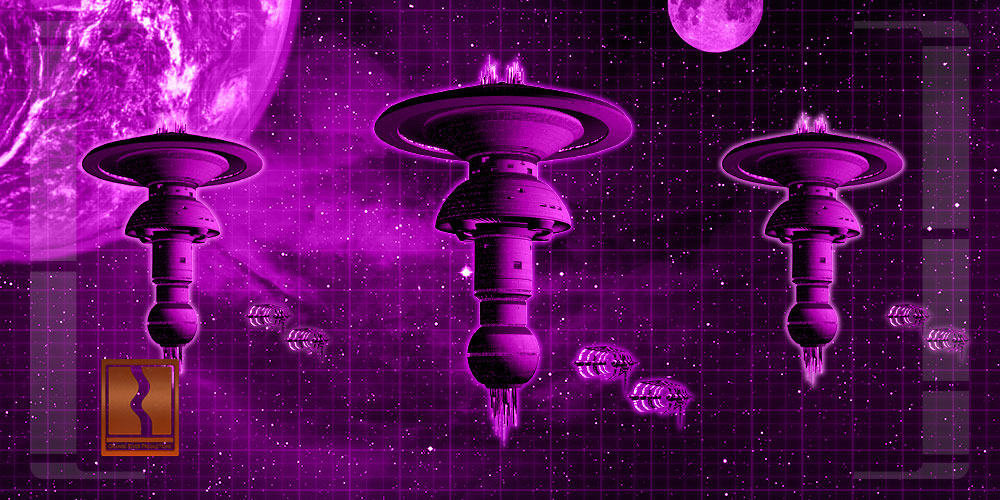

Either way, we learn that by the 23rd century, hundreds of Starbase’s exist throughout the Federation, some of which resemble Spacedock while others do not. Starbase’s such as Deep Space Station K-7, Starbase 375, and even Deep Space 9 have many of the same facilities, including docking bays and ports, but are often much smaller than Earth Spacedock.

Could We Actually Construct Something Like This In Real Life?

Well, one major technical consideration to keep in mind is how these space stations generate gravity. Just as with the propulsion, they most likely accomplish this the same way as starships: with gravity plating.

This gravity plating is one of the most “out-there” examples of Star Trek technology, up there with the warp drive. Indeed, more plausible designs for large space stations often depict them as circular or ring-shaped so they can take advantage of something called centrifugal force.

Centrifugal force is an inertial force derived from the angular velocity acting on an object with mass in a rotating reference frame. In Newtonian mechanics, it is described by the equation F = mω2r. A large rotating space station that rotates fast enough could generate enough centrifugal force to simulate 1g of gravitational pull just like we have on Earth. In addition to being featured in other sci-fi like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Babylon 5, and Mass Effect, this circular design has also served as the basis for a number of proposed real-world space stations like the Mars Gravity Biosatellite to study the effects of Martian gravity on mice.

This kind of artificial gravity is also a key component of the hypothetical O’Neill cylinder, a long tube-like space station concept that has appeared in movies like Interstellar. Proposed by American physicist Gerard K. O’Neill in 1976, O’Neill cylinders are artificial habitats that would be constructed using materials extracted from the Moon and asteroids in one of humanity’s early attempts at space colonization.

They’d consist of two sets of rings that rotate in opposite directions to cancel out gyroscopic effects, and they’d be 20 miles (32km) long, connected at each end by rods via a bearing system. While we haven’t built anything like this yet, and there are other engineering problems to consider, the science for generating artificial gravity in this way is quite well established.

There are very few examples of this in Star Trek, in large part because it’s much easier to film a simulated artificial gravity environment with flat topography than a 2001 style ring station. In-universe, the artificial gravity generated by “gravity plates” under every deck is made possible by manipulating the graviton, a theoretical particle associated with gravity.

We haven’t discovered the graviton, and it may not exist, but we have a pretty good idea of what it would look like if it does. It’s expected to be a massless boson with a particular spin, or momentum, that gives rise to the force of gravitation through an energy vector associated with the gravitational field, a curvature of spacetime.

Manipulating the graviton would be akin to generating a warp field, and the “artificial gravity generator” aboard starships and space stations would require energy just like anything else, but it would go a long way to helping simulate a more livable working space.

I’ve touched on a lot of subjects today in addition to discussing the major elements of what constitutes a Starbase, or, specifically, the space station portion of a Starbase. They really are magnificent structures with unique and iconic designs. They represent the greatest extent of what the Federation and humanity can give their sheer size and numerous applications.

Hopefully, I’ve done this topic justice in this video. Indeed, just as these orbital installations serve as waystations between the planets they orbit and the limitless space out there beyond the solar system, so too does the topic of Starbase’s serve as a launching point for other topics, like ship construction, artificial gravity, and more, all things I plan to cover in the future.

If you want to support my work even further, becoming a patron at patreon.com/orangeriver is a great way to do so.

Watch The Latest Video By Orange River Media Below

Thank you all so much for watching. This was definitely an overview kind of video, but as I said, hopefully, I did it justice. As always, I’m interested to hear your thoughts in the comments.

If you enjoyed this video, be sure to leave a thumbs up down below and don’t forget to share it. That stuff really helps me out. If you haven’t subscribed, be sure to do that as well and click the bell icon to receive all notifications.

I’ll see you in the next video…live long and prosper.